The early twelfth-century Povest’ vremennykh let (PVL or the Primary Chronicle) is in the foundations of mediaeval Russian chronicle-making culture. It depicts in most glorious terms the deeds of Grand Prince Sviatoslav Igorevich who ruled Kievan Rus between 946 and 972 according to its chronological scheme. Between 968 and 971 Sviatoslav waged two campaigns against Byzantines and Bulgarians. Certain bits of information found in the PVL about his campaigns tally with data found in the Byzantine sources, while others are genuinely of Rus origin. Amongst the latter is the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971. Its text is not found in the fifteenth-century Russian chronicles written in Novgorod. This piece shall deal with the textual issue as to whether the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971 and part of its preceding text were originally part of the PVL’s text and had been cut later in the Novgorod chronicles or it was not present in the historical sources composed prior to the PVL and inserted in its text. I shall explore this issue by examining one of A. Shakhmatov’s hypotheses that the Trinity manuscript of Novgorod Fifth Chronicle contained pieces of eleventh-century works that served in the composition of the PVL.

By surveying a number of manuscripts containing the Primary Chronicle, a plethora of eighteenth- to early twentieth-century scholars establish that the original work had been composed in Kiev in the 1110s.(1)

Mikhail Raev. The textual discrepancies amongst the mediaeval Russian chronicles…

Between the 1890s and the 1920s, A. Shakhmatov has revoked many of the interpretations proposed by his predecessors and offered plenty of explanations and hypotheses accommodating the textual imperfections, discrepancies, and contradictions in the examined manuscripts. He served as a source of inspiration to many further hypotheses and reconstructions by his later followers and critics. Ultimately he proposed that the Primary Chronicle was written in the Kievan Caves Monastery in the 1110s based on early chronicles such as the Drevneishii Svod (1030s) and the Nachal’nyi Svod (1090s). Based on an analysis of the Novgorod First Chronicle, Shakhmatov suggested that intermediary works like the Ancient Novgorod Chronicle (1030s), the Compilation of the 1070s, and a number of other works explain snippets of data supposedly transmitted over time by written records(2).

Shakhmatov considers that the Primary Chronicle was first copied in 1116 by Silvester, abbot of the St Michael’s Monastery of Vydobitsk. This version was further appended with several continuations. A manuscript copied by the monk Laurence in 1377 contained the best readings of these works(3). The second version of the Primary Chronicle, reproduced in 1118 in the Kievan Caves Monastery, has been amplified with a number of southern Rus continuations. Its copy had been kept in the Hypatian monastery near Kostroma. Its manuscript dates from the midfifteenth century(4). Since the original Primary Chronicle has not survived, its two basic versions and their related manuscripts are identified in the historiography as its second and third redactions(5).

All manuscripts containing the Primary Chronicle convey all four Russian-Byzantine treaties under annual entries for 907, 912, 945, and 971. They do not feature in existing thirteenth- to fifteenth-century manuscripts of the Novgorod First Chronicle. This work has two redactions: the older, preserved in a 1350s Synod manuscript, and the newer found in a number of fifteenth-century manuscripts such as the Commission’s and the Academy’s ones(6). As the first sixteen quires of the former, covering events up to 1016, are missing, Shakhmatov hypothesised their text could be identified in Trinity manuscript of the Novgorod Fifth Chronicle(7). Zimin and Nasonov have reaffirmed his hypothesis in the 1950s.(8)

Apart from the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971, the Novgorod First Chronicle is missing large excerpts from the Chronicle of George the

Monk, as well as other pieces of information found in the Primary Chronicle. Researchers have examined two theories. First, the Novgorod First

Chronicle could be delivering the text of earlier compilations to the Primary Chronicle. Second, the Primary Chronicle’s text might have been abridged in the Novgorod First Chronicle. A. Shakhmatov propounded the first theory, while S. Bugoslavskii found arguments in favour of the second. Given his personal reputation and authority, most of Shakhmatov’s followers elaborate on his grandiose scheme of Primary chronicle textual transmission, while a much smaller group of scholars furthers some arguments developed in Bugoslavskii’s antithesis(9).

To accommodate the inconsistencies and contradictions in the data provided by the available manuscripts, Shakhamtov offers a number of

hypothetical abridgments in the form of imagined treatises which he placed in pre-Primary Chronicle accumulation stages of historical information. One such work he claims to be an abridged version of the Chronicle of George the Monk which differed from the available Slavonic translation of the same work. Shakhmatov supposes that it was a version translated in Bulgaria(10). His colleague V. Istrin – who published the Slavonic translation of the Chronicle of George the Monk – disagrees on two major points with him. He argues that Shakhmatov’s stemma is too complex and proposes that there were not more than two individual chronicles prior to the Primary one; the rest, if proved, he considers their mere continuations(11). To back his conjecture, Istrin opposes the idea of a Bulgarian translation of the Chronicle of George the Monk and proposes a reduced version translated in Kievan Rus and named by him the Khronograph po velikomu izlozheniu(12). The introduction of such translation or treatise would not explain the Byzantine data outlined in the Primary

Chronicle’s text following 948, including the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971, since the extant Slavonic translation of the Chronicle of George the

Monk abbreviates at this point, as do many of its Byzantine manuscripts.

A much simpler explanation than hypothesising unrecorded Slavonic works would be to conjecture that a Byzantine Greek manuscript was used in the Primary Chronicle since some Byzantine manuscripts of the Chronicle of George the Monk convey it along with its post-948 continuation. The Chronicle of George the Monk (Γεώργιος Ἁμαρτωλός) itself was produced after 843 and its manuscript tradition is rather complex. It was appended with a continuation copied from the Chronicle of Simeon Logothete for 843 to 948. Some of these composite works continue with texts on Byzantine politics and warfare as late as 1143(13).

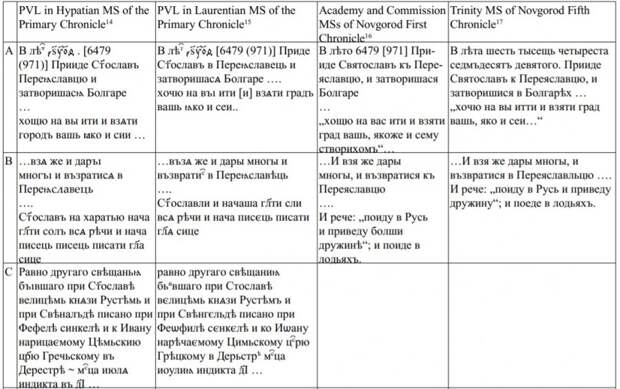

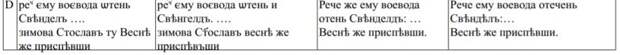

Here, I shall contribute to this discourse by exploring Shakhmatov’s proposal that the Trinity manuscript of the Novgorod Fifth Chronicle rendered the missing part of the older redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle. The paragraphs preceding and following the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971 in the main redactions of the PVL are collated below along with two manuscripts of the newer redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle and the Trinity manuscript of the Novgorod Fifth Chronicle.

Българско царство. СБорник в чест на 60-годишнината на доц. д-р Георги Н. Николов

Table: Collation of the PVL redactions along with the Academy and Commission manuscripts of the newer redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle and Trinity manuscript of the Novgorod Fifth Chronicle

Section A contains a text with same data and similar wording in all examined manuscripts. The texts of section B in the Hypatian and Laurentian redactions are identical in information and almost identical in phrasing. This text is edited and shortened in the newer redaction of the Novgorod First and Fifth Chronicles. They render an identical paragraph, suggesting that in the Fifth Chronicle it was faithfully copied from the First one. The editing of Primary Chronicle text concerns reworking part of section B and removing section C in the Novgorod chronicles. Section D is identical in all examined manuscripts. The missing text in the Novgorod chronicles is replaced by the connecting phrase, “и поиде в лодьяхъ“, which serves as a link between sections B and D. Based on collating these fragments, the Novgorod Fifth Chronicle is clearly a verbatim copy of the newer redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle. Given identical texts for some eleventh-century events in the older and newer redactions of the Novgorod First Chronicle, the similarity between the PVL and the latter for the same period, as well as almost identical texts of the 971 events as rendered in the newer redaction of the Novgorod First and Fifth Chronicles18, we may surely conclude that the older redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle contained a shortened version of the PVL text.

The following details are found both in the Primary Chronicle and the Novgorod Chronicles: Sviatoslav’s two Balkan campaigns; similarities in particulars such as the place name of Preslav, Sviatoslav’s speeches and Byzantine gifts; the Byzantine envoys sent to Sviatoslav; the rendering of identical leading characters such as Prince Sviatoslav and Sveneld; the Pecheneg ambush of Sviatoslav’s army. By cutting of section C of the PVL excerpt above in the Novgorod Chronicles significant portion of text and number of details are deleted such as: the transfer of warfare from Preslav to Dristra and the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971 with these details: Emperor John Tzimiskes (969–976), metropolitan Theophilos, month, year and indiction of its signing. All these pieces of information were most likely borrowed from a Byzantine manuscript depicting Sviatoslav’s Balkan campaigns in the PVL whose chronological set follows the basic chronology found in Byzantine sources(19). I find this explanation more plausible in terms of information transfer instead of the opposite,

i.e. that the missing details from the PVL in the Novgorod Chronicles signal a text prior to the former that has been further elaborated with them once reworked and inserted into the Primary Chronicle.

Editing texts and adapting them to commissioners’ requirements was a common mediaeval practice. It affected any manuscript as to its composition and arrangement of copied works. Occam’s Razor favours the simpler explanation of Bugoslavskii and his followers that the newer redaction of the Novgorod First Chronicle renders an edited and shortened text of the Primary Chronicle, while the Russian-Byzantine treaty of 971 was in the original composition plan of the latter’s author.

1) See the summary on the PVL composition, sources and dating published in: Словарь книжников и книжности Древней Руси. Вып. 1 (XI – первая половина XIV в.). Ред. Д. С. Лихачев. Ленинград, 1987, с. 337–343; as well as The Povest’ Vremennykh Let: an Interlinear Collation and Paradosis. ed. D. Ostrowski (Harvard Library of Early Ukrainian Literature: Texts, vol. 10). Cambridge, MA., 2003, p. XXI– XL.

2) А. Шахматов. История русского летописания, т. 1: Повесть временных лет и древнейшие русские летописные своды, кн. 1: Разыскания о древних русских летописных сводах. Санкт-Петербург, 2002, с. 23–30, 123–135, 270–358.

3) Лаврентьевская летопись. Ред. И. Карский. (Полное собрание русских летописей т. 1). Ленинград, 1926, с. IV.

4) Ипатьевская летопись. Ред. А. Шахматов. (Полное собрание русских летописей т. 2). Санкт-Петербург, 1908, с. IV–VIII.

5) Словарь 1987, с. 337, 340.

6)Новгородская первая летопись старшего и младшего изводов. Ред. А. Насонов. (Полное собрание русских летописей т. 3), 1950, с. 4–10.

7) Словарь 1987, с. 245–247

8) А. Зимин, А. Насонов. О так называемой Троиьком списке Новгородской летописи. – ВИ, 2 (1951), с. 89–91.

9) С. Бугославский. Повесть временных лет (списки, редакции, первоначальный текст. – В: Старинная русская повесть. Статьи и исследования. Москва-Ленинград, 1941, с. 7–37 (с. 34).

10) А. Шахматов. „Повесть временных лет“ и ее источники. – ТОДРЛ, 4 (1940), с. 11–150 (с. 41).

11) В. М. Истрин. Замечания о начале русского летописания. – ИОРЯС, 17 (1924), с. 222–251.

12) В. Истрин. Книгы временыя и образныя Георгия Мниха. Хроника Георгия Амартола в древнем славянорусском переводе. Текст, изследование, словарь. Петроград, 1922, c. 418.

13) A. Markopoulos. Sur les deux versions de la Chronographie de Symeon Logothete. – BZ, 76 (1983), p. 279–284 (p. 280).

14) Ипатьевская летопись, с. 58–62.

15) Лаврентьевская летопись, с. 69–74.

16) Новгородская первая летопись старшего и младшего изводов, с. 121–123.

17) Новгородская первая летопись старшего и младшего изводов, с. 523–524

18) Т. Вилкул. Новгородская первая летопись и Начальний свод. – Palaeoslavica, 11 (2003), p. 5–35.

19) Karyshkovskii’s works well encapsulate past research on the Byzantine sources and their major departures from the PVL, see П. О. Карышковский. О хронологии русско-византийской войны при Святославе. – ВВр, 5 (1952), с. 127–138; П. О. Карышковский. Балканские войны Святослава в византийской исторической литературе. – ВВр, 6 (1953), с. 37–71.

Mikhail Raev (Sofia, Bulgaria)

Свежие комментарии